Among the many obscure things that pop up on the internet, a Valentine’s Day celebration at San Diego State University over forty years ago is available on YouTube. Covered by local News 8 for its evening broadcast, the video was posted in 2019 within a throwback compilation. The scene, a sea of eager students blanketing the quad, is almost timeless. With their retro t-shirts and jeans and blown out hair, the year is unmistakable: it’s 1979.

Much of the decades-old footage is focused on about a dozen young men standing on a stretch of sidewalk, fully apart from the rest of their classmates. Most in the group are wearing shirts displaying the Greek letters of their fraternities. More than one is shuffling about nervously. These are the contestants, in a game to win a date. A young woman about their age is both the judge and the trophy.

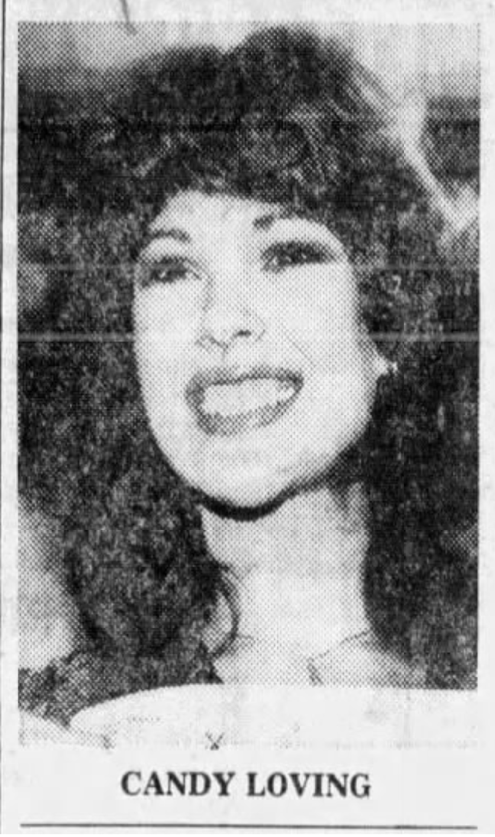

A song written about that particular young woman almost thirty years later says it all. “Little girls want candy. Little boys want Candy Loving.”

Candy Loving understood what it meant to be hopeful. A year earlier, at twenty-one, already married and working two jobs—as a waitress and in a dress shop—to cover her tuition as a journalism student, she entered a contest herself, one she thought might change her life for the better. While her husband urged her on, Ms. Loving wasn’t sure and waited until the last day for her tryout. She knew she was in the running when the initial interview, expected to last ten minutes, went on for an hour. It’s been said that after she was discovered at that casting call in Norman, Oklahoma, the contest was hers to lose.

Playboy’s 1978 search for their Silver Anniversary Playmate (“The Great Playmate Hunt”) was well-publicized and took the magazine’s representatives all over the country (and beyond). Young women were notified of casting calls through newspaper ads and other media.

Despite Ms. Loving’s stellar audition, the contest officially went on and as months passed, she was told she was one of 25 finalists, then one of nine, then four, then three. The contest came down to two contestants before Ms. Loving finally received the waited call. Rising above a field of almost 4,000 aspiring models, Ms. Loving was chosen as Playboy’s 25th Anniversary Playmate.

The issue was released in January 1979, at 410 pages, thick as a phone book and weighing one pound and eleven ounces, with Ms. Loving as the centerfold along with her featured pictorial, “Playmate Perfect.” She received a check for $25,000 and was set to tour the United States, Mexico and Canada.

A month after the Silver Anniversary issue hit newsstands, Candy Loving found herself on the lawn of San Diego State University. Then on hiatus from her senior year at University of Oklahoma, she was relatively new to the spotlight, although not nearly as shy as the pool of young men milling around her.

Returning to the video, Ms. Loving is seen making what looks like a hurried choice and the winner boldly seizes the moment and embraces her for a kiss. She’s surprised, but not flustered. Her poise was among the reasons she’d been selected for her role.

The last image on screen is of one young man grinning wildly while holding up his checkbook for the camera, thrilled to have met Ms. Loving and showing off her signature. In another time and place, he would have been in her Intro to Journalism class, looking for any excuse to be next to her, borrowing her notes.

It was unexpected, but likely inevitable, that I’d stumble upon the Great Playmate Hunt while researching post-Watergate America for my crime novel, a police procedural set in the late 1970s.

A sweeping, nationwide contest with all the promise of a Wonka Bar Golden Ticket was enough to draw me in. As I began trawling newspaper archives, I uncovered pages of advertisements for playmate auditions and write-ups by local reporters covering both Playboy representatives and the young women showing up at their casting calls. Major networks featured David Chan, the lead photographer on syndicated talk shows. After the announcement of Ms. Loving as the contest winner, there was even greater publicity for the many Silver Anniversary parties and dances and banquets, lasting well into the following year.

Playboy’s celebration of its first twenty-five years was effortlessly threaded into everyday American life, underscoring the magazine’s transformation from subversive upstart to media powerhouse. Deemed a pornographic publication at its launch amid the conservatism of the 1950s, Playboy had moved well beyond the narrow confines of “entertainment for men” and by 1979, it had attained a distinct voice that demanded attention. The magazine had long been recognized for its timeless journalism, publishing interviews that set the standard in the industry along with a celebrated advisor column and the highest tier of literary short stories. It was a cultural mainstay with just enough edge to keep it interesting. NBC put it pretty well in the ad copy for its series, The Playboy Club, set in the 1960s. “… a time and place in which a visionary created an empire, and an icon changed American culture.”

Going through the ’70s as a teenager, I’d been a huge consumer of both the news and pop culture. I read everything and watched way too much television, and yet other than knowing the magazine was available for purchase at most 7-Elevens (who could miss that?) Playboy was something I’d never much noticed. Not in the least.

Having been detoured into the world of late 1970s Playboy, I sifted through my research hoping to better understand the media empire that’d been a vital part of 20th Century America. Expecting to eventually come up with a paper trail of blatant misogyny and the magazine’s notorious commodification of women, what I found was something else entirely. A series of contradictions.

As the decade’s final year played out, feminists, who’d always viewed Playboy a pernicious enemy, reasserted their interest, and venom, in a formidable way. Among their maneuvers, the founders of the War on Pornography, a movement which saw Gloria Steinem leading a march through a pre-Giuliani Times Square littered with peep shows and triple X theaters and calling pornography “rape on paper,” made sure to fold Playboy in as a target. The same Playboy that’d just triumphantly stormed the country beginning with the Great Playmate Hunt. Among the claims was that “Playboy’s danger… lies in its educated audience” (The Minneapolis Star, June 21, 1979).

How was it possible for Playboy to have its casting calls featured as special interest articles in local papers (often running a full page) and then find itself caught on the fly paper of feminists protesting pornography? Trying to untangle Playboy’s place on polar opposite sides of mainstream acceptance, I came across familiar feminist rhetoric. But what most intrigued me was a noticeable silence.

The women who had the most to say on crucial topics like female agency, the models featured in the magazine, weren’t being heard. At least not in the higher echelons of the coastal media. Institutional feminists dominated the conversation of what it meant to be a feminist and how women were to be portrayed. Young women posing in Playboy intruded on the collective understanding. In a tale for the ages, women who ought to have been seen as free thinking were seen as stepping out of line. In today’s parlance, the word choice would be “problematic.” Aligned as they were with the juggernaut that was Playboy and all that the magazine contributed to American literature, art, politics, and, of course, the sex revolution, the models had all the potential to be “influencers” but instead, they’d been labeled as “less than” and effectively silenced. An entire group cancelled?

Several years after her first appearance in Playboy, when asked, as the journalist himself called it, “the obligatory question about feminism,” Candy Loving answered, “Part of feminism is allowing women the freedom to do what they want to do… When I won, my mother could have swayed me against it. She raised five kids by herself and I respect her very much. She said, ‘If you think it’s OK, I’ll be behind you.’ I have no regrets” (Boca Raton News, February 1, 1984).

The quote struck me as equally powerful and personal and it ought to have won the day in any serious discussion. What was taking place in the media, taking place among feminists, that papered over Ms. Loving’s beliefs? It’s a question I asked myself often, deep in the archives of old newspapers. I came up with a few thoughts. Questions about sexual equality and liberation are very much in the current moment, but the focus of my limited series of essays is 1979.

One last point. Looking back on what it meant to be a young woman coming of age in the wake of both the sexual revolution and second wave feminism, it’s easy to analyze/write about/judge the era’s journalists and cultural critics, here in the comfy BarcaLounger of hindsight. Since the late ’70s, there’s been a constant shifting of social and political norms pushing the dialogue on feminism forward: Demi Moore nude and seven-months pregnant on the cover of Vanity Fair; meaningful conversations on “slut-shaming” and all things social media; the full arc of third wave feminism. The context of the late 1970s is something to consider, but more often than not, reevaluating the narrative come down to common sense.

Continue reading

Click here to read the next issue in this series, about Playboy’s Prime Time TV specials from 1979: one with pajamas and roller disco and a visit to Hefner’s grotto and an array of special guests like James Caan and Cheryl Tiegs, TIME Magazine’s All-American Model; the other Playboy’s 25th Anniversary retrospect featuring many of the great writers who’d been featured in the magazine like Alex Haley, Ray Bradbury and poet (and three-time Pulitzer Prize winner) Carl Sandburg.

We’ll also start tracking the line in the sand Playboy drew for feminists that reignited their longstanding fury.

Episode Notes

This Week’s Recommendation

Valentine’s Day Throwback: SDSU students compete for date with Playboy Playmate

This Week’s Music

“She’s a Beauty” by The Tubes (on Spotify and Amazon Music)

“Candy Loving” by SSM (on Spotify and Amazon Music)

How interesting! Looking forward to diving in.

I recently purchased some Playboy magazines for my collage art projects and reflected on how complex the publication really was. From the vantage point of 2024, the models seem innocent and titillating. The cartoons though ...

yeesh. Much more disturbing. Great fiction, from big names like John Cheever and Margaret Atwood no less.