A Fresh Look on a 1973 Media Controversy

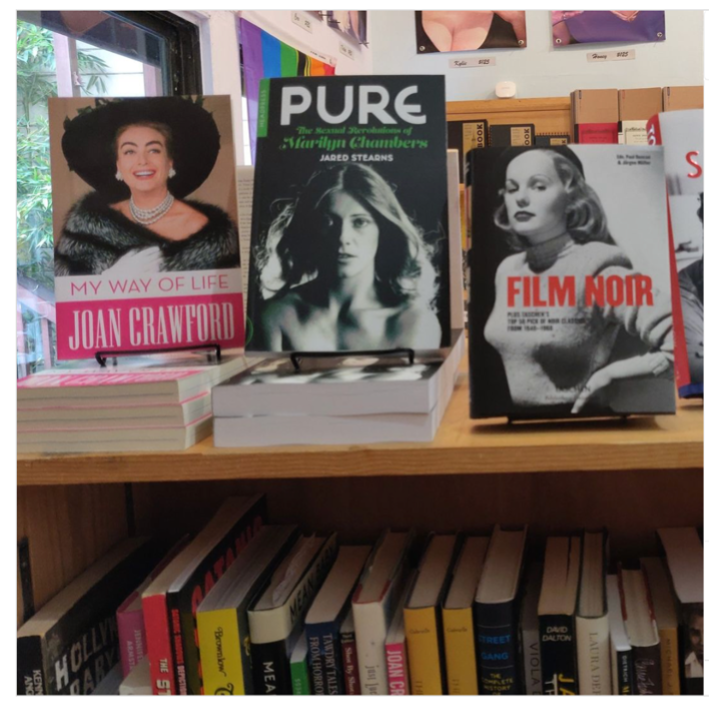

Pure: The Sexual Revolutions of Marilyn Chambers by Jared Stearns

“In many ways, Marilyn Chambers could only have become famous in the seventies.”

— Jared Stearns, Pure

Technically, her film debut was in the 1970 Barbra Streisand film, The Owl and the Pussycat, and her decades-long career included similar mainstream fare, but it was her starring role in the Mitchell Brothers’ Behind the Green Door (1972) that caused a sensation and propelled her into national headlines. This was the point when she became both famous and indelibly associated with X-rated entertainment. It was also the point when the young woman who’d been born Marilyn Briggs and raised in the leafy suburbs of Westport, Connecticut, became Marilyn Chambers.

In writing her biography, Jared Stearns, a longstanding and ardent fan of Ms. Chambers, who passed in 2009, sought to give life to the woman who was many things, including a wife, a mother, a sister, a daughter, as well as one of the standout cultural touchstones for the 1970s-era sexual revolution. It was a tall order, requiring that he introduce Ms. Chambers to a generation that had never heard of her, along with re-introducing her to a generation who had largely forgotten her. More than that, he tasked himself with portraying her as he found her: funny and smart and vivacious. Stearns evokes a version of Marilyn Chambers that challenges the preconceived notions set up for women who star in adult film. Through interviews with Ms. Chambers’s siblings and her daughter (with whom he’s struck up a deep friendship), he brings to life a human being, but also honors the woman “…woven into the fabric of American pop culture as both a symbol of and an avatar for the sexual revolution. She transformed an industry and forced important conversations about sexuality that continue today. Her contributions should be reconsidered, and her life as a woman in show business is one that still resonates.”

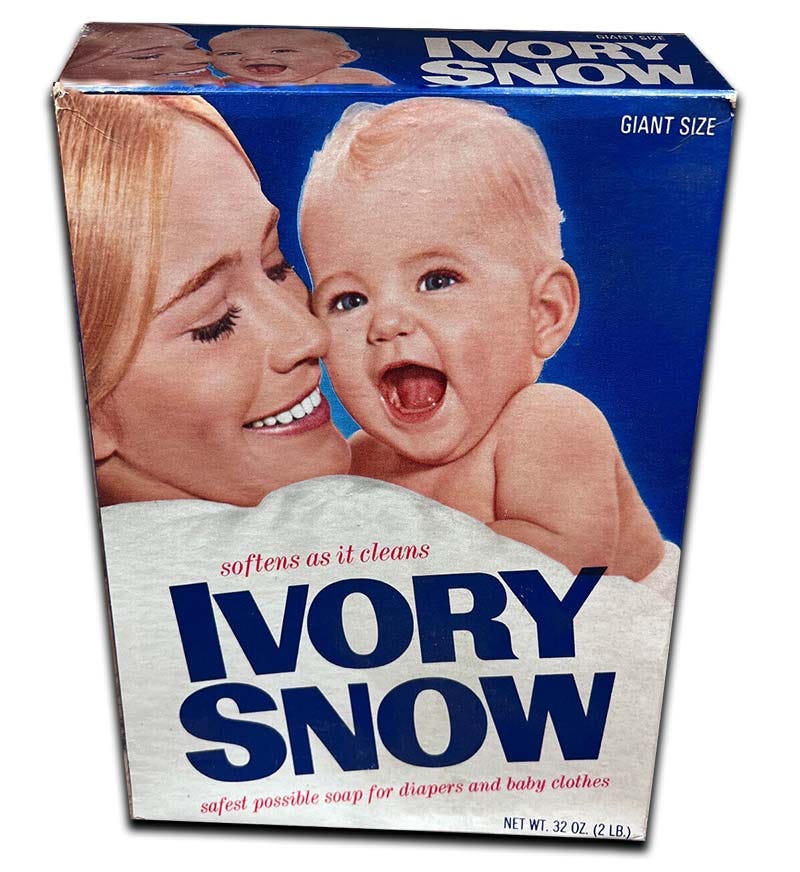

Marilyn Briggs was the youngest of three and popular in school; she competed in dive meets and other sports competitions, but never got the attention from her parents that she sought. Strikingly beautiful as a teen, she easily established herself in Madison Ave-level modeling. At the age of seventeen, she was selected above hundreds of other models to appear as the new face of Ivory Snow detergent. It was just another modeling job, one she soon forgot, but for the structure of her fee. She’d be paid the second half of the money she’d earned with the launch of the ad campaign and was told the boxes would take about two years to appear in stores.

After high school, she crossed the country seeking the fame California promised (and still promises) to photogenic young women. She found her way to San Francisco, which she’d mistaken for an entertainment capital on par with Los Angeles, where she met and married a bagpipe player (yes, you read that correctly).

The biography picks up with her answering an ad for “a major motion picture” and fatefully meeting Jim and Art Mitchell. That picture, Behind the Green Door, which would be buoyed by unlikely publicity, was the first adult film to screen at the Cannes Festival. Marilyn Chambers, who’d turned twenty-one the month before, was in attendance as the film’s star.

As Jared Stearns points out, her rise to stardom was the stuff of the 1970s, probably because it (quite improbably) began like this. After Behind the Green Door was filmed, but before it was widely released, Marilyn’s memory was spurred when she received the second half of her fee for her Ivory Snow modeling gig, which she casually mentioned to Jim and Art Mitchell. The media-savvy Mitchell Brothers waited until it would be too late for Proctor & Gamble to pull the detergent off the shelves, and then contacted the press to highlight Marilyn as the same young woman on the box and in their film.

As the Mitchell Brothers anticipated, an X-rated actress with the all-American, clean-cut looks that qualified her as the new Ivory Snow girl (its motto since 1895 was “99 and 44⁄100 pure”) caught national headlines.

The controversy, which made the rounds in nearly every newspaper, and included Ms. Chambers’s photograph as well as her comments in most articles, circled around the embarrassment to Proctor & Gamble, who immediately moved to “replace the soap boxes that carry a photograph of Miss Chambers cuddling a baby.”1 But the controversy also propelled her name into the national conversation so that she was famous for her X-rated work—perhaps too famous and perhaps too soon—before she could pivot into the other roles she was restless for.

Soon after her second film with the Mitchell Brothers, Chuck Traynor reached out to pitch a Las Vegas appearance—one that was originally intended for Linda Lovelace, the actress whom he’d steered into the film Deep Throat but had just divorced. Chuck Traynor would become Marilyn’s second husband and her manager. Though that physically and emotionally violent relationship enveloped her, a volatile and destructive time that takes up much of the biography, she still managed a long and varied career that had her staring in the David Cronenberg horror film, Rabid, appearing on Live with Regis and Kathie Lee in 1989, and headlining as lead singer in Haywire, a country and western band that performed in Las Vegas.

Sadly, her breaks into mainstream entertainment were mostly close calls and near misses. She lost out on a role in 1979’s Hardcore because she looked too all-American to be credible as an adult film star, and that was the irony of the media controversy that began her career. The wholesome good looks that ought to have defied her presence in an X-rated film.

Marilyn Chambers was the kind of person for whom the stars aligned in a way that had her taking a radically different path than most, and that’s the kind of story that’s always a good read. She comes across as a good person, who was honest, who was funny, who was smart, who adored her ultimate role as a mom. Film director John Waters, an avid critic of pop culture, describes it as “a really well-researched and fair biography about a woman who happened to do porn.”

While I was working on this book review, I began to think of Pure as the story of one woman, but also about the times that both made and influenced Marilyn Chambers; times when the American culture was in the throes of rapid change. The 1970s are often an overlooked and misunderstood decade, thought to lack the drama and panache of the 1960s. The civil rights movement, the women’s movement, the sexual revolution, and even the beginning of gay rights emerged in the 1960s, but much of that upheaval was occurring in the big cities and on the two coasts. The 1970s were the years when everything that was edgy and new was incorporated into the mainstream, all of the change finally percolating into everyday life.

What’s fascinating and so turbulent about the 1970s are the many tensions that surfaced as the culture began to experiment with a host of new guardrails. Marilyn Chambers was at the forefront in one arena, pushing the guardrails around both female sexuality and pornography as a growing form of mainstream entertainment. Some of the groundwork had already been set. The Summer of Love remains an iconic expression of open sexuality. Hollywood expanded what was acceptable in film with 1969’s Midnight Cowboy (Academy Award winner for best film and best director) and its graphic depictions of rape, prostitution and homosexuality taking it back and forth between X and R-ratings, and magazines like Playboy fully cemented in the mainstream. Still, there wasn’t anything close to a solid assent to these transformations.

Changes seen in big cities, and universities, and on the nightly news were moving threateningly close to small towns with their deeply entrenched values. This was the America that had stood helplessly watching the long hair and drugs they’d hated to begin with morph into the Manson murders, the perceived rise of black militants, an overall loose sexual morality, the Chicago Seven, and everything else that’d rose up in the ’60s. By 1971, with the previous ten years barely over, the decade was dissected in William L. O’Neill’s immensely popular, Coming Apart: An Informal History of America in the 1960s. The title is a huge clue as to the upheaval that was felt throughout the country. 1971 had also given “mainstream” America the hero they’d needed in the form of Dirty Harry. Clint Eastwood’s Harry Callahan may not have been the misogynist fascist some claim, but the film was unquestionably a reaction to the times.

What better place to understand the level of control small communities still had as late as the mid-1960s (and the hold on morality they feared they were losing) than in Meredith Hall’s tender and bruised recounting of “the steep price paid for one night on a beach with a boy.” In her essay, “Shunned,” Ms. Hall details a serene and happy childhood filled with Sunday school and close friends and unconditional love from her parents; a warmth that instantly evaporated one afternoon in 1965. At age 16, Ms. Hall was pregnant and the close-knit community that had embraced her, the one she had known and loved, brutally shunned her. In the same day, she was expelled from school and thrown out of her mother’s house. Her father and stepmother reluctantly took her in on the condition that she not show herself outside. Listen here as she describes the smallest freedom she found for herself, creeping out of the house in the chilling cold of a New England winter and sneaking into the woods where she lies down to make snow angels. After giving up her son for adoption at birth, she was then banished from her father’s home as well.

That was in 1965. Like many small towns in America, the 1970s saw Meredith Hall’s Hampton, NH begin to absorb the aftershocks of the sexual revolution. This isn’t to say that a new level of tolerance had permeated on a granular level into the culture, but see how the narrative, the zeitgeist had changed.

Five years after she’d been declared an outcast, the local drive-in was screening the X-rated Freedom to Love. Not only was the film shown at an outdoor theater, it was advertised on the community-interest page alongside the more routine Hampton area news.

To give a fuller window on the changes five years had made, the front page of that same paper ran the article, “Teenagers Can Best Help Their Peers in Trouble,” which began with these sentences: Who can know the fears of a high school girl who discovers she is pregnant? Who can understand the feelings of a youth who runs away from home? The article then describes Seacoast New Hampshire Call Me, Inc., a help line manned by a group of high school students seeking to help “their generation.”2

The creeping of the sexual revolution into the mainstream went like the gentrification of a neighborhood, which begins with one or two revitalized brownstones and then a decent sandwich shop and then no one remembers that aioli was once simply called mayonnaise. Kind of like that, really in no time at all, the front page of a local New Hampshire newspaper was advocating sympathy on behalf of “a high school girl who discovers she is pregnant.”

Marilyn Chambers and the media controversy that propelled her to fame was not the only bridge between the before and after, but she was a large part of it.

When Marilyn Chambers passed in 2009, The New York Times ran her obituary, with the first paragraph devoted to the controversy that made her: her photograph on the box of Ivory Snow and her performance in Behind the Green Door, which had “evoked stunningly contrasting portrayals of womanhood.”3

I wonder now if “contrasting portrayals of womanhood” is the correct take on the Ivory Snow frenzy. The Times credits Behind the Green Door “with helping establish the mainstream market for pornography,” but that momentum had begun in the 1960s. That was the gestalt of the 1970s: the breakneck speed advances of the sexual revolution, where porno chic had Jackie Onassis attending screenings of Deep Throat and Marlon Brando starring in the X-rated Last Tango in Paris right after he’d been Don Corleone in The Godfather. The 1970s continued the disruptions of the prior decade. What had not been disrupted in either decade was the fault line that separated the good girl and the bad girl. That barrier seemed to have held. So much so that even in fairly recent interviews, Christie Hefner was still explaining Playboy’s upstart views on female identity.

How I felt about [Playboy] was consistent with how the readers and the writers and the employees felt about it, which was that it is very easy for men to both desire and admire women [emphasis added].

~ Christie Hefner, 9 to 5ish with theSkimm, May 29, 2018

What Marilyn Chambers was revealing as the fresh-faced young woman who appeared in Behind the Green Door was this reality: hers were not “contrasting portrayals of womanhood.” They existed within the same woman and the question to the American public was this: Is this where the sexual revolution was supposed to end up? It was one thing to accept ever more graphic sexuality in film when the stars were throwaway women—the Candy Barrs (and later Linda Lovelaces) of the world—and women in the suburbs were merely sitting in the theater. It was quite another, and very large next step, when the suburban girl was now on film. The revelation that adult film stars were persons who could once have been anyone’s neighbor or friend was a stunning reality check. So stunning that one adult film star who was notable simply for having actually existed in real life earned a write-up in Esquire, in a way that “My-uncle-the-70s-dental-hygenist” never would have.

From the perch of the 2020s, the cultural significance of Marilyn Chambers’s seeming duality takes on layers and depth. Then, the pairing of Ivory Snow and Behind the Green Door was about the marketing disaster to Proctor & Gamble. With the distance of many years and added perspective, it was about the young woman who became the newest chapter in the sexual revolution that no one saw coming. Marilyn Chambers held up a mirror to the American public. The silvered glass reflected her image side-by-side with a culture that was primed for her appearance yet reeling in confusion now that she’d arrived.

Is this what you really wanted? Is this how far the sexual revolution was supposed to go?

Running her obituary, The Montreal Gazette Headline chose a different route than The New York Times with the headline, “Marilyn Chambers, Star of ‘Rabid,’ Dies at 56.” It sets the tone for another way to remember her. If you want to know about the young woman who walked into the fire, took on the persona of Marilyn Chambers and became a cultural touchstone but also the real person—her relationship with her parents and siblings, her hopes and dreams and role as a mom—it’s all there in Jared Stearn’s meticulously researched and lovingly rendered book. The telling of a very American story.

Episode Notes

This Week’s Recommended Reading

This Week’s Music

“Over the Rainbow” by Eva Cassidy (on Spotify and Amazon Music)

Just One More Thing

What event from the public zeitgeist do you recall most vividly?

Dayton Daily News, May 30, 1973.

The Portsmouth Herald, October 3, 1970.

The New York Times, “Marilyn Chambers, Sex Star Dies at 56,” April 14, 2009.

Wow! Marilyn Chambers is a name I hadn’t thought about in years! Fascinating piece, Melanie, the 70s were their own rich time, now you’ve got me thinking about public access tv and constantly running into Robyn Bird on the street!