In this niche series about “toxic masculinity,” it seems Westerns and the archetypal cowboy are a rich place to poke around. The film depictions were popular entertainment, but also seen as complex mythologies “setting up generations of American boys with a strong, proud, and often problematic role model for manhood.”1 The reckoning of the Western-hero icon as “often problematic” began in the 1970s and continues to echo among contemporary thought leaders on what it means to be a man. Concepts of “Lone Ranger” masculinity vs. relational masculinity emerged as the women’s movement gained momentum, prodding needed explorations on gender imbalance and the place for women in the culture, but also causing men to face questions of their own identity.

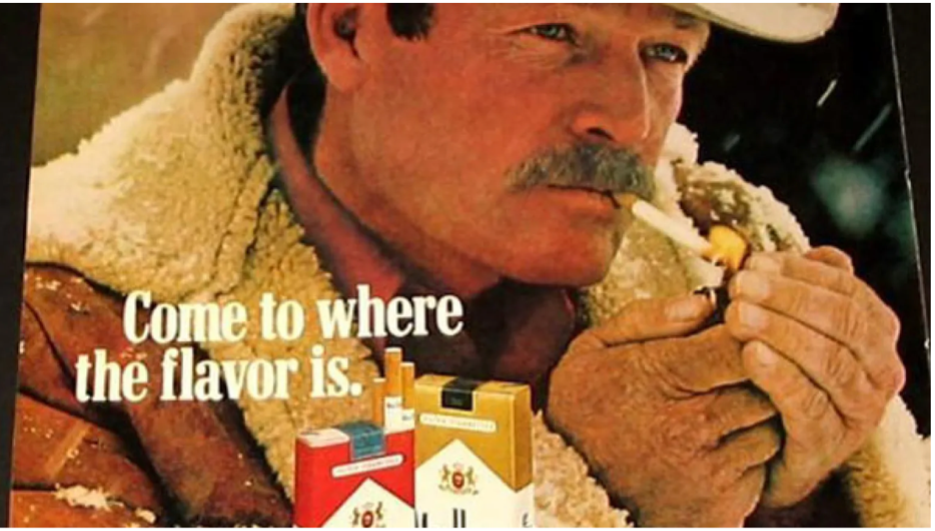

Even while the “sensitive new age guy” was entering the culture, the Marlboro man remained a powerful image throughout the 1970s, mixing the cowboy mystique with other “guy things”: cars, guns, sports, money, the conquest of women. Images in keeping with an America still dominated by white men. Though men were not then the sole stewards of the culture, this was a patriarchal society, and they had control of the big-ticket items: government and finance and media and academia. In the later years of the twentieth century, as women’s rights became a cultural norm, a few standards began to evolve. Women educated men as to their value in society and nudged past them on their way into law schools and board rooms. It began to be tacitly understood that men had been somewhat poor stewards of the culture; being the architects of a power system that prevented women from getting credit and where men could fire a stewardess for gaining weight. Traditional manhood, in the language of second wave feminists, had been too long defined as an identity that “depend[ed] on violence and victory.” The Marlboro man easily fit within feminism’s growing scrutiny, taking much of the Western traditions that imagery represented into the crossfire.

Explorations of what it meant to be masculine (or overly masculine) may have begun in the 1970s, but the movement was ongoing, with at least two national reporters attending the 1990 Wildman Gathering, an event where “males could come together in semiwilderness, apart from women, to get in tune with their bodies and their feelings.”

Texas Monthly noted that “in November 1988, there were something like seventeen women’s resource centers in Austin and not one place for men.” The uneven attention along with a very long national conversation meant to quash male chauvinism (a term soon to be swapped out for toxic masculinity) might be underlying what’s now seen as a larger crisis for men.

Reflecting on all the women’s movement had to take on, it wasn’t realistic that their ire at masculinity would be re-evaluated with surgical precision. But we can look back now on what exactly was devalued. Taking the very narrow lens on the cowboy myth (both as a specific instance of male behavior under scrutiny by feminists and as a microcosm of wholesale efforts to redefine masculinity), we can ask, were Westerns stories of pure chauvinism and violent gunslinging or were honor and duty and courage in the face of evil equally at play? Were these complicated mythologies?2

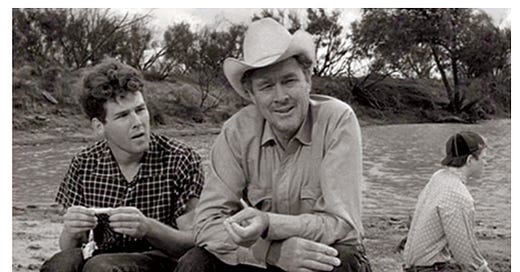

If anyone understood the cultural and historical relevance of the classic Western, it was Peter Bogdanovich, who’d been a film historian and archivist before leaving New York for LA. In 1970, he began preparations to film Larry McMurtry’s semiautobiographical novel, The Last Picture Show, a coming-of-age set against the passing of small-town Texas life, and was obsessed with having Ben Johnson play the pivotal role of Sam the Lion, the moral center of the fictional Anarene.

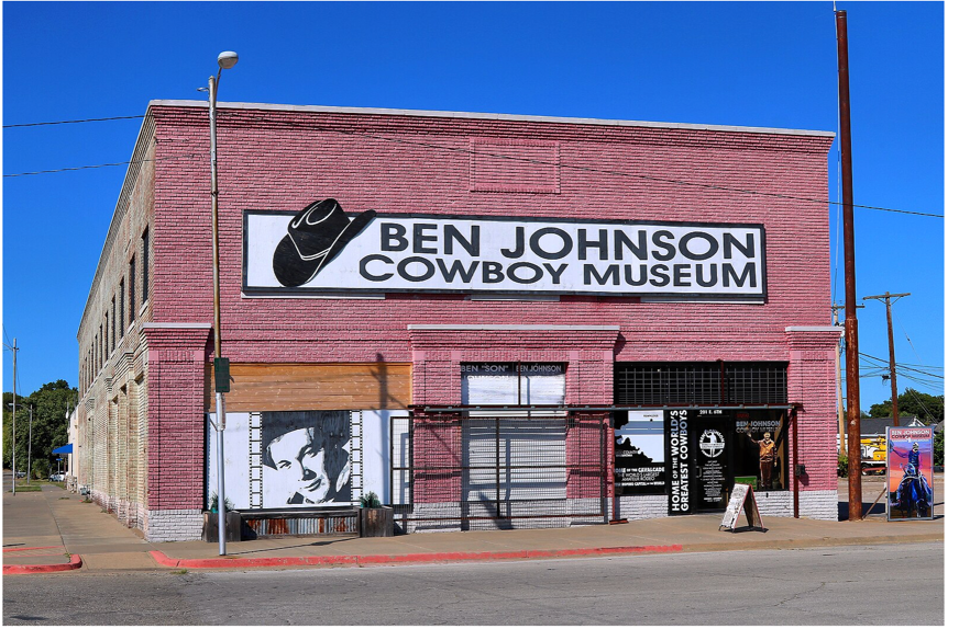

Born in 1918 on the Osage Indian Reservation, Francis Benjamin Johnson, Jr. grew up on a working ranch. He’d been charged with delivering horses to Howard Hughes for the 1939 film, The Outlaw. After herding the animals to California, he stayed on as a wrangler and a stuntman. Over time, he became a member of John Ford’s stock company, appearing largely in supporting roles. Known for doing his own stunts in the 1950 John Wayne classic, Rio Grande, he rode roman style (standing astride a pair of horses, a foot on the back of each), galloping and clearing a jump at full speed.

That combination of skill and daring might explain how, decades into his film career, he was a World Champion Rodeo Roper (team roping, 1953). The title of the 1996 documentary, Third Cowboy on the Right, is a nod to Johnson’s status most often as a character actor: the making of a film on Johnson’s life a nod to his significance within the Western genre.

To the late actor, Bill Paxton, “growing up in Texas and Oklahoma, Ben Johnson was more famous than John Wayne to some of us.”

Johnson initially turned down the role in The Last Picture Show, objecting to the “dirty language” the script called for and saying his part had too many words, and only accepted after John Ford personally intervened.3 For Bogdanovich, “[h]aving Ben Johnson was the real thing.” A rancher and rodeo cowboy who projected “warmth and grit, believably embodying a vision of the American West.”

Tom Ford, the designer turned film director, spoke of the actor’s “rugged gentility” and saw “such sensitivity, such kindness in his face."

In many ways, Sam the Lion was an image, like an iconic photograph telegraphing everything you need to know. Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother.” Children running from napalm in Vietnam. Johnson’s Sam the Lion was an understated strength and character within a particular kind of man. Having spent years doling out advice to Sonny and Duane, the bored teenagers who spend much of their free time in both his diner and poolhall, Sam becomes irate when he finds the two have taken the mentally disabled Billy to lose his virginity to a local prostitute. Duane slumps in the back seat of a car to avoid Sam’s eye, while Sonny is devastated that he’s been called out. The older man’s disappointment in Sonny is a near mortal blow, his reaction sharply contrasting with the others, who barely take note of Sam’s raging judgment.

Their cruelty, as they preyed on the more defenseless, is what we today call toxic masculinity. Sam, stripped of the gunslinger motif and its frequent bravado, portrayed exactly the defense of the less powerful that defined the Western. It’s all there in the scene. What it meant to be a man was handed to the culture in one of the defining films of the 1970s. Not just a masculinity that embodied caring for those who were weaker, but a masculinity that embodied modeling that responsibility to restless teen boys. When Sam forgives Sonny, it allows him to stay close and steer the boy in a better direction. Ben Johnson/Sam the Lion was a “cowboy for all seasons.”

We think of Westerns as having fallen prey to the rout of the Marlboro man, where a type of two-dimensional male bravado came to define the genre and then all the cowboy stories fell out of fashion. The fallout, of course, goes deeper. Pushing the Western into the corner gives permission; whenever it’s easier to use shorthand to define and then dismiss things that are complicated. Westerns were very much stories about white men. But they were always more than their surface, and even when deemed “problematic” an understanding of their nature has remained, a thing hiding in plain sight.

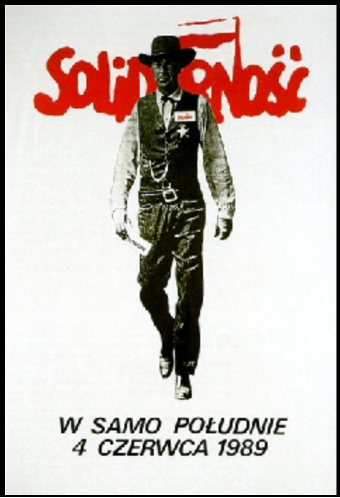

As Poland, under Lech Walesa, sought to escape from Soviet dominance, a poster showing Gary Cooper as the lone sheriff in High Noon circulated with a red Solidarity banner and the date of the election. Years later, Lech Walesa explained the poster and how it had never lost its strength:

“Cowboys in Western clothes had become a powerful symbol for Poles. Cowboys fight for justice, fight against evil, and fight for freedom, both physical and spiritual. Solidarity trounced the Communists in that election, paving the way for a democratic government in Poland. It is always so touching when people bring this poster up to me to autograph it. They have cherished it for so many years and it has become the emblem of the battle that we all fought together.” (emphasis added)

Episode Notes

This Week’s Recommended Listening

For more about the westward expansion through a modern lens, The Rest is History, “The Wild West”

From the Karina Longworth Podcast, You Must Remember This, an alternate (feminist?) view on the making of The Last Picture Show—Polly Platt: The Invisible Woman |“It wasn’t sexism, then”

This Week’s Recommended Music

"Theme From An Imaginary Western (Album Version)" by Mountain (on Spotify and Amazon Music)

Just One More Thing

Is there a myth, fable, or legend that’s stayed with you?

The Psychology of the Western: How the American Psyche Plays Out on Screen (McFarland & Co. 2008).

“Shane’s Technicolor Morality,” Austin American Statesman, March 11, 2001.

Johnson won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, the BAFTA for Best Actor in a Supporting Role, the Golden Globe for Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture, the National Board of Review Award for Best Supporting Actor, and the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Supporting Actor.

I’m definitely watching The Last Picture Show again after reading your rich and thoughtful piece, Melanie.

This series if off to a great start, Melanie. I really appreciate you writing this. It helps, of course, that I had watched (more than once) The Last Picture Show and, while I hadn't thought it through as you have here - that character - and many other similar masculine characters - have made an impression on me to really value all the positives of the so-called masculine traits. It probably helped that I worked almost exclusively with men for a lot of my career so I saw the many positives of masculinity often.