“The flutter of wings, the sounds of the nights, the shadow across the moon as the Nightbird lifts her wings and soars above the earth into another level of comprehension, where we exist only to feel. Come fly with me, Alison Steele, the Nightbird…”

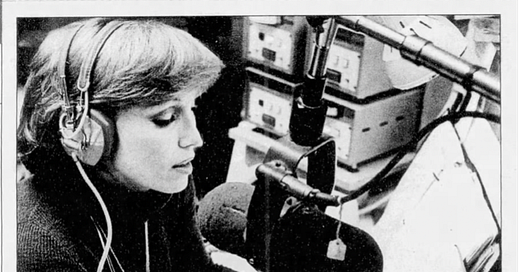

When Alison Steele signed on for her nightly shift, she offered her listeners an invitation: “Come fly with me.” And if her poetry wasn’t enough to keep you from turning the station, there was her voice. To say it was distinctive is to never have actually listened to her. The syntax and careful articulation were her own, yet her voice fit into every noir cliché. Smokey and honeyed and sultry. A voice that could only be described in relation to some hard drinking liquor. Bourbon in a cut glass tumbler. Night Train Express straight out of the bottle. Oh, and cigarettes.

When I briefly entertained the idea of posting audio clips of my Substack, Alison Steele was among my very first thoughts, stirring up memories of late-night radio.

There isn’t much published about her early life. In the newspaper accounts when she died, even in The New York Times, her early years were a line of two at best.

But that’s probably as it should be. How many New York stories are just like that. The whole point is to arrive in the city, fully formed; nothing behind you.

It was 1966 when she arrived. Not necessarily in Manhattan, since she was a native New Yorker (born Ceil Loman), but in the DJ booth as Alison Steele. By 1968, she was calling herself the Nightbird and ready to take her place as queen of late-night radio. She was central to the burgeoning format at stations like WNEW where she, along with a handful of other DJs, were pioneers in unscripted programming. Like other free form mediums—jazz, abstract art—the creative had to know the rules in order to break them. And Alison Steele knew the rules. She was the first woman to win Billboard’s FM Personality of the Year (1976) and an inductee in the Radio Hall of Fame.

But it was the conversation with her audience that she’s known for. What her one-time colleague, Vin Scelsa recalled in his eulogy for her. “In her undying devotion to her audience, Alison was unique. She was one of the last purveyors of the Utopian, communal vision of radio.”

The All-American Disc Jockey

During the Golden Age of American Radio, the 1930s and ’40s, it had been the medium for all news and a wide swath of entertainment; FDR’s fireside chats, shows picked up from the old vaudeville circuit, and the advent of soap operas like The Guiding Light, which debuted in 1937.

After television took over, where even soap operas migrated (The Guiding Light lasted on TV another 57 years), radio was news and sports and music. Commentary was restricted and the music was repetitive with a focus on the Top 40. Against these norms, Adrien Cronauer of Armed Forces Radio Services rebelled—reading censored news and playing rock and roll to the troops in Vietnam in the mid sixties. His irreverence inspired the perfect role for Robin Williams and the DJ booth became the perfect medium of the comedian/actor’s free form, ad-libbing.

Along with progressive rock and more niche, experimental music, Adrien Cronauer-style improv from radio personalities (a format often called underground) had been gaining momentum throughout the 1960s as more and more DJs were having real conversations with their listeners.

Looking back at his first successful feature, American Graffiti, the 1973 film that established George Lucas in Hollywood and made Star Wars possible, Lucas said this about Wolfman Jack, who makes a cameo, but pivotal, appearance:

Teenagers had a very personal relationship with the disc jockey… It’s interesting because it pre-dates the Internet and things like Facebook, where you have very intimate relationships with people you’ve never even met. I was fascinated by the fact that for a lot of teenagers, their closest friend, their closest confidant, the one person they really cared about in the world, was the disc jockey.

The Nightbird’s Perch

Though she started as a kind of gimmick when five women were hired for WNEW-FM, the gimmick didn’t last, although Alison Steele did.1

When women were a rarity in radio, like all of broadcasting, Alison Steele fit effortlessly into the WNEW-FM rising classic rock format; a blend of unscripted dialogue and DJ-chosen music; a radical departure from AM Top 40. She began her nights with Andean flute music and frequently brought her French poodle, Genya, with her to the studio. She played all the great rock of the day, Mountain and the Allman Brothers and the Grateful Dead, and layered in things like British folk-singer Sandy Denny’s cover of a Sammy Cahn standard.

She’d also layer in poetry, reading Poe and Wordsworth and Ginsberg and Shakespeare and some of her own. She took calls from her listeners. She spent the graveyard shift chatting with her audience and sharing her philosophy, which was optimism, sprinkling in her response to negative energy. “It’s like a cloud in the sky passing by. They always do, you know.”

Alison Steele had a feel for the DJ booth, but she also had a feel for the other side of it, as if she were speaking to some version of herself; the alone-in-her-room-with-her-radio-tuned-to-WNEW-FM side. And she knew exactly what if felt to be in that space, whoever you were.

There are 237 Comments posted on a YouTube clip of Alison Steele’s 1977 Valentine’s Day program; personal notes on her perfect-for-midnight voice and the music she introduced, but also many like this: “I listened to Alison all through high school. I would leave my stereo on all night and let her voice lull me to sleep. I’d wake up briefly to ‘Court of the Crimson King’ or the Strawb’s ‘Benediction,’ and then drift back to sleep.” And this from the WNEW-FM archive: “I remember listening to her late nights. She had a way of reaching out and making [it] seem like it was the two of you just grooving together like old friends.”

Alison Steele enjoyed her shift because the night was mysterious. It made for great conversations and great music. But things, of course, change.

As the culture moved forward, a different variety of talk radio was rising, most prominently Howard Stern. In 1979, Alison Steele signed off for the last time at WNEW-FM and moved to television, initially as an announcer for the soap opera, One Life to Live.

Though she didn’t stay in television, after doing production work for a show on CNN, she returned to radio (looking for an intimacy that wasn’t available to her anywhere else), her move from WNEW-FM had to have been a signal, portending the end of a particular kind of radio show, not only hers but for all of FM. Over the next decade, DJs moved around between stations that all toyed with different formats—always more conventional and often going back to fixed playlists. The halcyon days of unscripted dialogue and eclectic music would slowly ease away.

Vin Scelsa, a fixture in New York radio, lasted in the improv format the longest. He eventually landed at WFUV (the voice of Fordham University) and kept his show until retiring in 2015. He and his show were throwbacks to the once rich FM radio format that was commonly free of set playlists and pat dialogue. Vin Scelsa was warm and companionable, and I’d once heard him use the phrase “bee in your bonnet.” Given his proud blue collar Jersey roots, often going by the nom de plume, “Bayonne Butch,” he improbably led book discussions. On his recommendations, I was first introduced to both Denis Johnson (Fiskadoro) and T. Coraghessan Boyle (World’s End) and it was his review that led me to E.L. Doctorow’s Loon Lake. At his retirement, the last of the lot—he'd stayed around long enough to segue into a podcast with his daughter, Kate—it was cause for reflective think pieces in the New York Times and The New Yorker. There was no particular reason that I’d stopped listening to him regularly but by then, I had. Like an old friend I’d lost track of, I was sorry and full of regret when I learned his final show had aired.

What I missed was more than him personally. His form of radio took me back to the programs that shaped my teenage days and steered me through high school and into college. What we’d all listened to. It had taken me years to understand what a gift that programming had been.

The force of those DJs, with that hold on their listeners, a generation of us, has me thinking of community and intimacy and how they’ve played off each other across an assortment of mediums, ever since Guglielmo Marconi harnessed radio waves and mastered wireless transmission: the eventual dominance of television, Ham radio (which differs from the 1970s CB radio craze kicked off with Smokey and the Bear), the Hubble Space Telescope, sign language with Koko the gorilla, and onto Silicon Valley that’s brought us social media, where, as George Lucas points out, “you have very intimate relationships with people you’ve never even met.”

All the ways we want to reach out to each other.

The word I often hear used to describe Substack, the latest community-building social media endeavor, is “authenticity” and I wonder if that was Alison Steele’s secret sauce, combined with the medium uniquely suited to her talent. These are her words:

I thought there must be a lot of people…that needed something to relate to in the middle of the night and if I could create some kind of camaraderie, a relationship between myself and the rest of the night people, then it would be more than just music.

No surprise, her pre-dawn chatter is described as “a shared secret” with her listeners: to be a part of her audience was to be part of “a charmed circle.”2 That was true, whether you experienced her on the air or you were one of the callers who phoned the studio and had a personal conversation with her.

Though she was mostly too late at night for me—I wasn’t one to fall asleep to her gently reading poetry—there was something about Alison Steele and her singular voice/presence/unknown particles that’s seared itself. What comes back when I think of her now, what always struck me about her program, was the sense she was pulling back the curtains on a New York apartment and letting us peek into the window, and whenever I did listen in, welcomed as part of her charmed circle, Alison Steele was a portal; sharing a glimpse of a life I didn’t yet know was possible.

In a world craving intimacy, you can click on a YouTube link and close your eyes and experience her voice wrapping around you. Her voice made her iconic but there was something else that reached her listeners. The certainty that she knew each of us.

Episode Notes

Vin's journey to WNEW in the 70's, including unemployment and a misguided stopover in Long Island. Dave Herman, Scott Muni, Alison Steele, and WNEW's brief moment with an all-female DJ lineup. (Listen on Soundcloud or Apple podcasts)

This week’s Music

Alison Steele’s frequent sign off:

“Flying” by The Beatles (on Amazon Music and Spotify)

Additional Source Material

Pioneering DJ Donna Halper, of Quincy, to be inducted into Broadcasters Hall of Fame

Entry on Alison Steele in the Biographical Encyclopedia of American Radio

Blog post and comments section paying tribute to Alison Steele

1991 Daily News article about female late-night radio hosts

Just One More Thing

All questions and comments are welcome, but here are some thoughts for this week:

Have you found intimacy or connection in social media?

“End of a Myth – WNEW Finds Girls Can Spin Discs,” The Record, August 9, 1966.

“The Call of the Nightbird,” Citizen’s Register, June 29, 1990.

Loved Alison Steele! Great post, Melanie!

Radio station KEXP has unscripted DJs who are responsive to listeners, and fans do feel a personal connection to them and the station. It's great!