Dirty Harry is one of those names that evokes an immediate reaction. Even if you’ve never seen a Dirty Harry film (there are four), you likely know the eponymous main character, played by Clint Eastwood. You likely know the cold-hard-stare persona and you almost certainly know the most famous line from the rule-bending detective (spoken as he stares down a suspect, Smith & Wesson in hand), “Go ahead, make my day.”

While researching Second Wave Feminism, I came across a YouTube clip, “Dirty Harry on Feminism and Women’s Quotas.”

Given the general perception of Harry Callahan (aka Dirty Harry), the title alone had me thinking this would be a diatribe on the ills of feminism. Sweeping intolerance. That’s long been the take on both the character and the films.

Dirty Harry (1971) was a shockwave of intense police violence. An assault against both authority and crime, the film ushered in a new era. Harry Callahan became a recognizable character in the American story that was taking shape in the 1970s. The zeitgeist captured on screen was seen as the middle-American response and unapologetic pushback to the freedoms unleashed in the prior decade. Civil rights and the sexual revolution and women’s liberation.1 Given the extent of the violence (the American Civil Liberties Union and other civil rights groups attacked the film for glorifying police brutality) it’s no surprise the word “fascist” is often thrown about as a descriptor. Misogyny also creeps in.

But the four-and-a-half minute YouTube clip I viewed was a little different than expected. Taken from The Enforcer (1976), which is third in the Dirty Harry series, the scene is early in the film, after Harry has been called to task for his most recent use of excessive force. The rogue detective has been taken off homicide and assigned to personnel. He’s shown sitting in on a committee interview of Kate Moore, played by Tyne Daly, for the position of inspector. Moore has been on the police force for nine years, mostly in clerical positions, but she’s been pushed to the front of the line under a new “quota” system seeking inclusivity in hiring. Familiar territory? It’s as if the past forty-nine years were just a blur.

The plain takeaway from the committee scene isn’t that Harry had a knee-jerk reaction to the female recruit; one that belied a low opinion of women. Harry was asking a simple question: is it wise to prioritize quotas over skill? What I saw was Harry not willing to virtue signal. He pressed an issue he deemed significant (should police assignments be merit based) and was confrontational with Moore, posing a tough (perhaps bullying) question. The fact pattern in Harry’s hypothetical was salacious, it might well have been mere bullying, but Moore chose to ignore any hints that it was a direct insult to her, parsed through the scenario he’s set up, and gave him an answer displaying her impressive knowledge of the law. So ultimately, it’s Harry’s question that lets her distinguish herself as more than a token hire. More to the point, it’s the scene, as written, that lets her distinguish herself as more than a token hire.

Yet that scene, where he is freely thinking out loud on the issue of technical competence and saying what was actually in his mind led to reviews finding The Enforcer “the most misogynistic and violent of the series...which is saying something.”

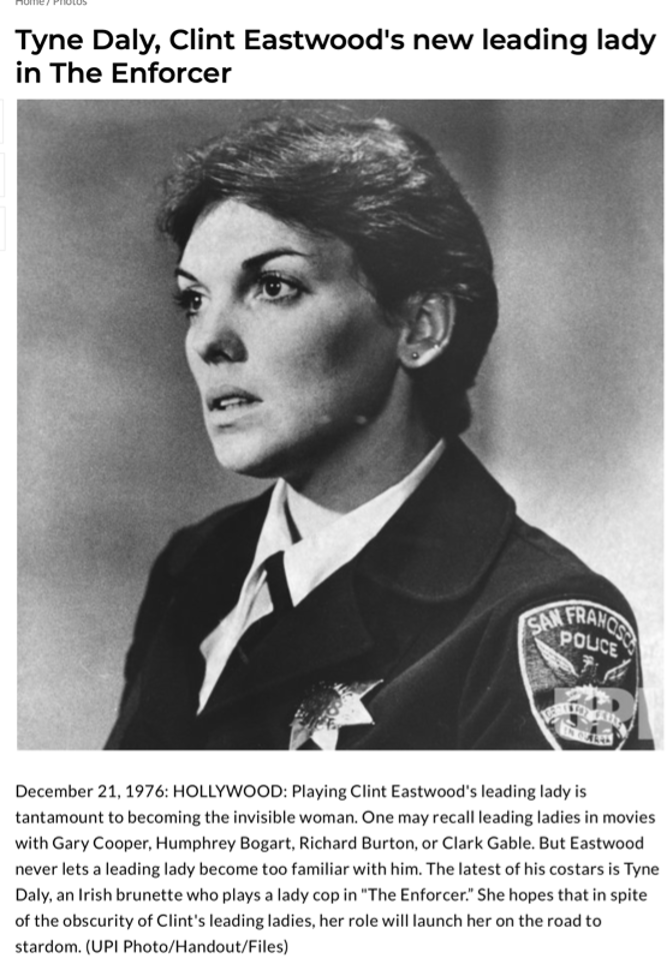

The jabs at Dirty Harry went beyond the scene and its critics. On its release, the press was more than eager to shred Tyne Daly as just another “invisible woman” in a Clint Eastwood film.

Decades later, Eastwood and Dirty Harry often remain linked in one, not particularly favorable, persona, whose iconic status “is attributed to a conservative longing for national confidence, power, and social order, all seemingly eroded by foreign military defeats and domestic civil rights and protest movements.” It’s a view that keeps Dirty Harry—and The Enforcer—in an anti-feminist light (“Hollywood’s post-Vietnam tendency to reclaim the unexamined masculinity of the damaged hero, who finds redemption not through introspection but only through ‘cathartic’ acts of violence.”)

With his swaggering violence, the character was without doubt displaying a full-on contempt of something. He’s as complex as you want him to be. A response to the corruption of government exposed in Vietnam (and soon to be on full display via Watergate) and that made him “the seminal ‘70s antihero.” Perhaps? There’s a discourse to be had on Dirty Harry and masculinity and the back-and-forth waves of progress versus a return to conservatism that roiled the 1970s. He wasn’t benign by any definition. But as I focused more on the YouTube clip, what became more and more interesting was the mistaken critique of The Enforcer as proof of Harry as a toxic male with “a low opinion of women in the work force.”

Because in the film, Kate Moore more than held her own with Dirty Harry.

Rewatching The Enforcer, I found Kate Moore to be smart and capable. She is also a complete rookie, so she makes rookie mistakes (she positions herself behind a handheld rocket launcher and only avoids being incinerated by backfire when Harry pulls her away; she retrieves a briefcase that’s been thrown by a suspect into a dumpster, never realizing it contains a bomb as she runs through the city, clutching it to her chest). Her inexperience, her flaws, made her multi-dimensional and real.

I wasn’t alone in finding her the standout. Even in 1976, she was the highlight for more than one reviewer. A “heroine of steel.” What made the portrayal so powerful to me was that Kate Moore was anything but spunky.

This was a thing in the 1970s. Women were facing down men who did hold a low opinion of them in society, and particularly in the work force. Many times, women had to be more competent to be taken seriously.

That reality became an unfortunate trope. The very real need for women to excel somehow morphed into the need to portray women as flawless and that in itself made the portrayals almost cartoonish.

Crime novelist Karin Slaughter laid it out in her 2014 thriller, Criminal. A dual time-line police procedural that alternates the present with 1975 when a pair of female patrol officers are hunting down a serial killer, their first actual case. They’re physically harassed by the men they work with. They interview witnesses in tenements strewn with drugs and garbage and vomit. They get their asses kicked by the suspect. And ticking in the back of their minds is the keen awareness their work is nothing like “the plot of a television sitcom where two plucky gals stick their noses where they don’t belong and end up escaping through wit and humor.”

This is why Kate Moore is awesome, other than pointing her own Colt Diamondback (2” barrel, snub-nosed version) and looking every bit as badass as Clint Eastwood. Kate Moore is not plucky.

While I was pondering the question of what Dirty Harry had to do with women’s lib, I came across a quote in the memoir No Angel, where ATF special agent Jay Dobyns recounts an undercover assignment that led to his being fully patched (voted in as a full club member) by the Hells Angels. While trying to recruit a female officer to work with him on the case, she’s cautioned that the motorcycle gang was misogynist. Her answer was direct.

“At least the Angels wore their sexism on their sleeves."

I often find things I wished I said. This went a little bit further. It was a clean assessment that knit together a few thoughts that had been floating around in my mind untethered. The quote made me think about virtue signaling and female agency and the fake feminism in the 1970s that was spreading spunky, cartoonish heroines in film and on TV (see Karin Slaughter, above). Compare that with the real thing in Kate Moore.

As he’s paired with Kate Moore, Harry grows to respect her, not because she was the plucky caricature of female competence that was the staple of Hollywood, but because her character was written as a good cop—smart and determined to make up for her lack of experience in the field—and because Harry was written as a man who was willing to open his mind.

Kate Moore might have been the quota hire for the San Francisco Police Department, but her character wasn’t a quota hire for Malpaso (Clint Eastwood’s production company). Kudos to Tyne Daly, who turned down the role three times and, once she ultimately accepted, had sway on the development of her character. Kudos to the men in charge who wanted an actress of her caliber and went with the character she was creating.

Kate Moore was a revelation for me, overtaking the question of whether Dirty Harry was a misogynist, which seems like a less compelling exploration when placed side by side with the woman Tyne Daly brought to life.

There’s something in her defying the usual Hollywood roles, like my hero, Emma Peel.

There’s something in the transgression.

Episode Notes

This Week’s Recommended Readings

“The Storytelling of Clint Eastwood” by

“Men and Guns, Part Two: ‘Dirty Harry’” by

This Week’s Recommended Viewing

The Mary Tyler Moore Show’s first episode; Lou Grant tells us what he thinks of spunk

This Week’s Recommended Music

“Just A Girl” (on Spotify and Amazon Music)

Just One More Thing

Thoughts on Dirty Harry?

Cinema Speculation (Quentin Tarantino, 2022).

Wonderful, Melanie, I need to go back and watch The Enforcer again. I love Emma Peel, too!

I haven't read this yet but looking forward to it! I always loved Harry. Ok, edited - now I have. He had 5 Harry Callahan movies: Dirty Harry, Magnum Force, The Enforcer, Sudden Impact (filmed in Santa Cruz!) and the Dead Pool. As you can tell, I am a Clint Eastwood fan and I loved the character. I recently saw that YouTube clip that you feature and I thought he was quite reasonable. Did you ever see Tightrope? It is a quasi-Callahan movie in that he plays a guy just like Harry, but he has sexual kinks. It gives a whole different view of a Harry-like character. Here's an article about it: https://www.slashfilm.com/1692357/clint-eastwood-trick-direct-one-best-movies-tightrope/ I recommend that movie if you haven't seen it.